Recall from the previous chapter that inheritance is the aspect of OOP that facilitates code reuse. Specifically speaking, code reuse comes in two flavors: inheritance (the "is-a" relationship) and the containment/delegation model (the "has-a" relationship). Let's begin this chapter by examining the classical "is-a" inheritance model.

When you establish "is-a" relationships between classes, you are building a dependency between two or more class types. The basic idea behind classical inheritance is that new classes can be created using existing classes as a starting point. To begin with a very simple example, create a new Console Application project named BasicInheritance. Now assume you have designed a class named Car that models some basic details of an automobile:

// A simple base class. class Car { public readonly int maxSpeed; private int currSpeed; public Car(int max) { maxSpeed = max; } public Car() { maxSpeed = 55; } public int Speed { get { return currSpeed; } set { currSpeed = value; if (currSpeed > maxSpeed) { currSpeed = maxSpeed; } } } }

Notice that the Car class is making use of encapsulation services to control access to the private currSpeed field using a public property named Speed. At this point, you can exercise your Car type as follows:

static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("***** Basic Inheritance *****\n"); // Make a Car object and set max speed. Car myCar = new Car(80); // Set the current speed, and print it. myCar.Speed = 50; Console.WriteLine("My car is going {0} MPH", myCar.Speed); Console.ReadLine(); }

Now assume you wish to build a new class named MiniVan. Like a basic Car, you wish to define the MiniVan class to support a maximum speed, current speed, and a property named Speed to allow the object user to modify the object's state. Clearly, the Car and MiniVan classes are related; in fact, it can be said that a MiniVan "is-a" Car. The "is-a" relationship (formally termed classical inheritance) allows you to build new class definitions that extend the functionality of an existing class.

The existing class that will serve as the basis for the new class is termed a base or parent class. The role of a base class is to define all the common data and members for the classes that extend it. The extending classes are formally termed derived or child classes. In C#, you make use of the colon operator on the class definition to establish an "is-a" relationship between classes:

// MiniVan 'is-a' Car. class MiniVan : Car { }

What have you gained by extending your MiniVan from the Car base class? Simply put, MiniVan objects now have access to each public member defined within the parent class.

Note Although constructors are typically defined as public, a derived class never inherits the constructors of a parent class.

Given the relation between these two class types, you could now make use of the MiniVan class like so:

static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("***** Basic Inheritance *****\n"); ... // Now make a MiniVan object. MiniVan myVan = new MiniVan(); myVan.Speed = 10; Console.WriteLine("My van is going {0} MPH", myVan.Speed); Console.ReadLine(); }

Notice that although you have not added any members to the MiniVan class, you have direct access to the public Speed property of your parent class, and have thus reused code. This is a far better approach than creating a MiniVan class that has the exact same members as Car such as a Speed property. If you did duplicate code between these two classes, you would need to now maintain two bodies of code, which is certainly a poor use of your time.

Always remember, that inheritance preserves encapsulation; therefore, the following code results in a compiler error, as private members can never be accessed from an object reference.

static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("***** Basic Inheritance *****\n"); ... // Make a MiniVan object. MiniVan myVan = new MiniVan(); myVan.Speed = 10; Console.WriteLine("My van is going {0} MPH", myVan.Speed); // Error! Can't access private members! myVan.currSpeed = 55; Console.ReadLine(); }

On a related note, if the MiniVan defined its own set of members, it would not be able to access any private member of the Car base class. Again, private members can only be accessed by the class that defines it.

// MiniVan derives from Car. class MiniVan : Car { public void TestMethod() { // OK! Can access public members // of a parent within a derived type. Speed = 10; // Error! Cannot access private // members of parent within a derived type. currSpeed = 10; } }

Speaking of base classes, it is important to keep in mind that C# demands that a given class have exactly one direct base class. It is not possible to create a class type that directly derives from two or more base classes (this technique [which is supported in unmanaged C++] is known as multiple inheritance, or simply MI). If you attempted to create a class that specifies two direct parent classes as shown in the following code, you will receive compiler errors.

// Illegal! The .NET platform does not allow // multiple inheritance for classes! class WontWork : BaseClassOne, BaseClassTwo {}

As examined in Chapter 9, the .NET platform does allow a given class, or structure, to implement any number of discrete interfaces. In this way, a C# type can exhibit a number of behaviors while avoiding the complexities associated with MI. On a related note, while a class can have only one direct base class, it is permissible for an interface to directly derive from multiple interfaces. Using this technique, you can build sophisticated interface hierarchies that model complex behaviors.

C# supplies another keyword, sealed, that prevents inheritance from occurring. When you mark a class as sealed, the compiler will not allow you to derive from this type. For example, assume you have decided that it makes no sense to further extend the MiniVan class:

// The MiniVan class cannot be extended! sealed class MiniVan : Car { }

If you (or a teammate) were to attempt to derive from this class, you would receive a compile-time error:

// Error! Cannot extend // a class marked with the sealed keyword! class DeluxeMiniVan : MiniVan {}

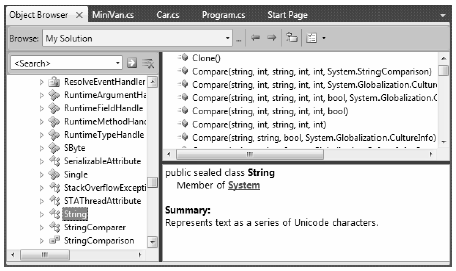

Most often, sealing a class makes the best sense when you are designing a utility class. For example, the System namespace defines numerous sealed classes. You can verify this for yourself by opening up the Visual Studio 2010 Object Browser (via the View menu) and selecting the String class within the System namespace of the mscorlib.dll assembly. Notice in Figure 6-1 the use of the sealed keyword seen within the Summary window.

Figure 6-1. The base class libraries define numerous sealed types.

Thus, just like the MiniVan, if you attempted to build a new class that extends System.String, you will receive a compile-time error:

// Another error! Cannot extend // a class marked as sealed! class MyString : String {}

Note Structures are always implicitly sealed. Therefore, you can never derive one structure from another structure, a class from a structure or a structure from a class. Structures can only be used to model standalone, atomic, user defined-data types. If you wish to leverage the Is-A relationship, you must use classes.

As you would guess, there are many more details to inheritance that you will come to know during the remainder of this chapter. For now, simply keep in mind that the colon operator allows you to establish base/derived class relationships, while the sealed keyword prevents subsequent inheritance from occurring.